Best Architecture for DataStage to Databricks Migration

By a Principal Data Architect & Migration Lead

I’ve spent the better part of two decades in the data trenches. The first fifteen were dominated by tools like DataStage, building robust, high-volume ETL systems for global enterprises. The last ten have been focused on designing and deploying large-scale data platforms on Databricks. I’ve led multiple migrations from the former to the latter, and I've seen firsthand what leads to a resilient, cost-effective platform versus what creates a sprawling, unmanageable, and expensive mess.

This isn't another marketing piece about the "magic" of the lakehouse. This is a pragmatic, opinionated guide on architectural decisions that will make or break your migration.

1. Introduction: Architecture, Not Tools, Decides Success

The single biggest mistake I see teams make is believing a DataStage to Databricks migration is a tool-for-tool replacement. It is not. It is a fundamental paradigm shift. Success is not determined by a conversion utility that turns a DataStage job into a PySpark script. Success is determined by an architecture that embraces the core principles of the cloud-native world.

Why DataStage Mental Models Fail in a Spark-Native World

DataStage, like its peers, encourages a specific mental model:

- Job-centric: The unit of work is the "job"—a visual, compiled binary that runs on a dedicated engine.

- Monolithic: The engine, storage, and metadata are tightly coupled in a server-based architecture.

- Stateful by Nature: Parameter sets, sequence state, and persistent datasets are core to its operation.

- Abstracted Compute: You tune the job, not the underlying cluster. The engine is a black box.

Applying this model to Databricks is a recipe for disaster. It leads to monolithic notebooks, unmanageable dependencies, and runaway costs. You cannot treat a distributed, code-first, ephemeral compute platform like a perpetual, on-premises ETL server. The architecture must change.

2. Design Principles for a Modern Data Platform

Before we draw a single box, we must agree on the principles that govern our decisions. These are non-negotiable for any enterprise-grade platform I design.

- Metadata-driven, Not Job-driven: Your pipelines should be dumb; your metadata should be smart. The flow—source, transformations, sink—should be defined in a configuration repository, not hardcoded in hundreds of notebooks. This is the single most important shift from the DataStage paradigm.

- Decoupled Compute and Storage: This is the cloud's gift. We leverage it fully. Data lives in cheap object storage (ADLS, S3). Compute (Spark clusters) is ephemeral, spun up on demand for a specific task and torn down immediately after.

- Cost-aware by Design: Cost is an architectural attribute, not an accounting problem. We design for cost control from day one using ephemeral clusters, right-sizing, and strict governance.

- Governed, Observable, and Auditable: From day one, every piece of data and every job run must be traceable. We must know what ran, when, what data it read, what data it wrote, and who has access to it.

3. Source & Ingestion Layer

This layer is about getting raw data into the lakehouse with minimal transformation and maximum fidelity.

-

Handling Sources:

- RDBMS (Oracle, SQL Server, DB2): For batch ingestion, the Spark JDBC connector is sufficient for moderate volumes. However, for large-scale, performance-sensitive ingestion, it often becomes a bottleneck.

- Trade-off: Do not build a complex, multi-threaded, parallel JDBC framework in Spark. The operational overhead is immense. Instead, for high-volume tables, use a specialized tool (Qlik Replicate, Fivetran, Debezium, Striim) for Change Data Capture (CDC). The tool cost is almost always cheaper than the engineering and support cost of a fragile, home-grown solution. Batch remains a viable option for smaller, non-critical tables.

- Files (CSV, JSON, Parquet): This is Databricks' bread and butter. The primary tool here is Auto Loader. It incrementally and efficiently processes new files as they land in cloud storage. It's more scalable and robust than custom file-watching scripts or trigger-based functions. Use it.

- Mainframe Feeds: The most reliable pattern remains a file-based handoff. The mainframe job drops a file (often with an EBCDIC codepage and a COBOL copybook) onto a pre-agreed storage location. Our ingestion pipeline picks it up from there. Trying to connect directly to the mainframe is a world of pain involving specialized drivers, security exceptions, and operational fragility.

- RDBMS (Oracle, SQL Server, DB2): For batch ingestion, the Spark JDBC connector is sufficient for moderate volumes. However, for large-scale, performance-sensitive ingestion, it often becomes a bottleneck.

-

Raw/Bronze Zone Design:

- The target for all ingestion is the "bronze" layer.

- Structure:

bronze/source_system/table_name/ - Format: For structured sources, I now default to Delta Lake even in bronze. The overhead is minimal, and the benefits (schema evolution, time travel for debugging ingestion issues) are significant. For semi-structured or unstructured data (like raw JSON logs), storing the raw file and using Auto Loader with schema inference is fine.

- Principle: The bronze zone is immutable append-only. We are capturing the raw truth from the source system at a point in time. No joins, no business logic. The only "transformation" allowed is data type casting or PII-masking if mandated by compliance.

4. Processing & Transformation Layer

This is where the core business logic happens. It's also where most DataStage-to-Databricks migrations go wrong.

The Anti-Pattern: The 1:1 "Lift-and-Shift"

The temptation is to take a DataStage job like Job_Customer_Dim_Load.dsx and create a notebook called Job_Customer_Dim_Load.ipynb. This is a catastrophic error. It leads to:

* Massive code duplication (reading sources, handling errors, logging).

* Inability to test individual transformation steps.

* A brittle web of notebook-to-notebook dependencies.

The Correct Approach: A Metadata-Driven Framework

Instead of monolithic jobs, we build a library of reusable transformation functions and a generic "engine" notebook that executes them based on metadata.

-

A Simplified Metadata Model: Imagine a few tables (can be Delta tables, or in a relational DB like Postgres/Azure SQL).

Pipelines:pipeline_id,pipeline_nameTasks:task_id,pipeline_id,task_order,source_id,target_id,transform_idDataSources:source_id,path,format,optionsTransformations:transform_id,function_name,parameters

-

The "Engine" Notebook: A single, parameterized notebook, say

run_spark_task.ipynb, does the following:- Accepts a

task_idas a parameter. - Reads the metadata for that

task_id. - Loads the source DataFrame(s) using information from

DataSources. - Looks up the transformation function name and parameters from

Transformations. - Dynamically calls the appropriate function from a shared library (e.g.,

from my_transforms import join_with_customer; df = join_with_customer(df, params)). - Writes the resulting DataFrame to the target defined in the metadata.

- Accepts a

-

Handling Complex Logic: What about DataStage's complex transformers or custom routines?

- Rewrite them as Python or Scala functions that accept and return a Spark DataFrame.

- These functions become part of your reusable transformation library.

- This approach makes logic unit-testable, reusable, and independent of the orchestration flow.

5. Storage & Delta Lake Architecture

We use the standard Medallion Architecture, but with specific, experience-based rules.

- Bronze (Raw): As described in the ingestion section. Append-only, source-aligned.

- Silver (Cleansed, Conformed): This is where the real modeling happens.

- Purpose: Integrate, clean, and conform data. We resolve data quality issues, deduplicate, and create our enterprise view of key entities (e.g., a master

customerstable, a canonicaltransactionstable). - Operations: Heavy use of

MERGE INTOis the norm here to handle inserts, updates, and deletes (SCD1/SCD2). - Structure: Organized by business domain or subject area, not by source system (e.g.,

silver/sales/transactions,silver/customer/customers).

- Purpose: Integrate, clean, and conform data. We resolve data quality issues, deduplicate, and create our enterprise view of key entities (e.g., a master

-

Gold (Curated, Aggregated):

- Purpose: Business-level aggregates, dimensional models, or feature tables for BI and ML consumption.

- Structure: Highly denormalized and optimized for read performance. These tables directly power Power BI, Tableau, or other reporting tools. Example:

gold/sales_reporting/monthly_regional_summary.

-

Partitioning & Table Design: This is critical for performance and cost.

- Rule of Thumb: Partition by the column most frequently used in

WHEREclauses. This is almost always a date or timestamp field (partition by ingestion_dateorpartition by event_date). - Avoid Over-Partitioning: Partitioning by a high-cardinality column (like

user_id) will create millions of tiny files, killing read performance. This is the "small file problem," and it's deadly. - Z-Ordering: After partitioning, use

ZORDER BYon columns frequently used for joins or filtering within a partition (e.g.,customer_id,product_sku).

- Rule of Thumb: Partition by the column most frequently used in

6. Orchestration & Workflow Architecture

DataStage Sequences are powerful. Replicating their robustness requires deliberate design in Databricks Workflows.

- Mapping Sequences to Workflows: A DataStage sequence becomes a Databricks Workflow DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph). A job activity in a sequence becomes a task in the workflow.

- The Framework in Action: Each task in our workflow is a call to the same generic "engine" notebook (

run_spark_task.ipynb), but with a differenttask_idparameter. This makes the orchestration layer incredibly clean and simple. The logic is in the metadata, not the workflow definition. - Dependency Management: Workflows handle task dependencies natively. For passing data between tasks (e.g., a record count), use Task Values.

- Restartability and Idempotency: This is non-negotiable.

- Every task must be idempotent: running it twice with the same input must produce the same output state.

- Delta Lake's

MERGEandoverwriteoperations are naturally idempotent and are your best friends here. - Design workflows for partial failure. If a task loading one of five dimension tables fails, you should be able to fix and re-run only that single task, not the entire workflow. Our metadata-driven design makes this trivial.

7. Metadata, Lineage & Governance

This is what separates a data swamp from an enterprise data platform.

- Centralized Metadata Repository: As mentioned, this is the brain of our framework. I've had success using a simple Azure SQL Database or AWS RDS (PostgreSQL) for this. It's transactional, easy to query, and decouples the metadata from the Spark environment. You can even use Delta tables, but a relational DB often provides better tooling for management.

- Lineage:

- The Goal: Answer the question, "If I change this source column, what BI reports will break?"

- The Solution: Databricks Unity Catalog (UC) is the strategic answer. It automatically captures column-level lineage for notebooks and workflows operating on UC-managed tables.

- The Reality: UC is not magic. To make the lineage useful, you must supplement it. Our metadata-driven framework is perfect for this. During a pipeline run, we use the UC API to add comments and tags to the target tables and columns, such as

source_system=SAP,pipeline_run_id=xyz,quality_checked=true. This enriches the technical lineage with operational and business context.

- Security & Access Control: Unity Catalog is the only way to do this at enterprise scale. It provides a central place to manage

GRANT/REVOKEpermissions on catalogs, schemas, tables, and even columns and rows (with row filters and column masks). This replaces the old world of managing file-system ACLs and separate database permissions.

8. CI/CD & Deployment Architecture

Manual deployments are for hobby projects. In the enterprise, everything must be automated.

- Source Control: All code (notebooks, Python libraries, SQL scripts) and configuration (Terraform, workflow JSON) MUST live in a Git repository (GitHub, Azure Repos). Databricks Repos provide the direct integration to link a workspace to Git.

- Environment Promotion: A typical setup includes

dev,test, andprodDatabricks workspaces.- A developer works on a feature branch in the

devworkspace. - A pull request to the

mainbranch triggers a CI pipeline (e.g., in GitHub Actions, Azure DevOps). - The pipeline runs automated tests (e.g.,

pyteston transformation functions). - On merge to

main, a CD pipeline triggers. It uses the Databricks CLI or Terraform Provider for Databricks to deploy the assets (notebooks, workflow definitions, cluster policies) to thetestand thenprodworkspaces.

- A developer works on a feature branch in the

- Infrastructure as Code (IaC): Use Terraform to define and manage Databricks workspaces, clusters, policies, permissions, and storage mounts. This ensures your environments are reproducible, auditable, and easily recoverable.

9. Performance & Cost Architecture

In the cloud, performance and cost are two sides of the same coin.

- Cluster Strategy: The Golden Rule

- Job Clusters for Production Workloads: Each orchestrated workflow run gets its own, purpose-built "Job Cluster." This cluster is defined in the workflow, spins up, runs the job, and terminates immediately. This provides 100% workload isolation and the most predictable cost model.

- All-Purpose Clusters for Development & Ad-Hoc Analysis: A small number of shared, "All-Purpose" clusters can be used by developers and analysts. These should have aggressive auto-termination policies (e.g., 30-60 minutes of inactivity).

- Workload Isolation: Using Job Clusters is the ultimate isolation. Don't run multiple production jobs on a single, large All-Purpose cluster. A rogue query can starve critical ETL of resources.

- Cost Guardrails:

- Cluster Policies: These are your seatbelts. Define policies that enforce mandatory tagging (e.g.,

cost_center,project), limit the maximum cluster size (DBUs/hour), and enforce a maximum auto-termination timeout. No user should be able to launch a 100-node cluster that runs all weekend by mistake. I've seen it happen. Cluster policies prevent it. - Monitoring: Use the system tables (if available) or build your own dashboards to monitor DBU consumption per tag, per user, and per job. Question every spike.

- Cluster Policies: These are your seatbelts. Define policies that enforce mandatory tagging (e.g.,

10. Validation & Parallel Run Architecture

You can't simply turn off DataStage and turn on Databricks. You need a period of parallel runs to build trust.

- Data Reconciliation Strategy: Don't eyeball the data. Build an automated reconciliation job.

- This is a separate Spark job that reads both the final DataStage target (e.g., an Oracle table) and the new Databricks Gold table.

- It calculates and compares:

- Row counts.

- Checksums or hashes on a concatenation of all non-nullable columns for a given business key.

- Summations of key numeric columns (e.g.,

SUM(sales_amount)).

- The results are written to a reconciliation dashboard. You should aim for 100% match before even considering a cutover.

- Cutover Planning:

- Run both systems in parallel for at least a few business cycles (e.g., two weeks to a month).

- Use a phased approach. Cut over one subject area or a group of pipelines at a time. Start with the less critical ones. A "big bang" cutover is exceptionally risky.

- Rollback/Fallback Pattern: The parallel run IS your fallback. If the Databricks pipeline fails post-cutover, the DataStage pipeline has been running and the legacy target is still up to date. You can simply re-point downstream consumers back to the old target while you debug the Databricks failure.

11. Common Architecture Anti-Patterns to Avoid

If you see your teams doing these things, raise a red flag immediately.

- The "Lift-and-Shift" Job: Creating one notebook per DataStage job. This is the #1 cause of failure.

- The Monolithic "God" Cluster: Running all development, ad-hoc, and production jobs on one massive, always-on All-Purpose cluster. This is a cost and stability nightmare.

- Ignoring Metadata: Hardcoding paths, table names, and transformation logic directly in notebooks. This creates an unmanageable, brittle system.

- Treating Databricks Like an On-Prem Server: Leaving clusters running 24/7. Not using ephemeral job clusters. This negates the primary cost advantage of the cloud.

- DIY Orchestration: Using cron jobs or Airflow without deep integration. Databricks Workflows are tightly integrated with the platform's identity, security, and cluster management. Use them.

12. Real-World Architecture Example

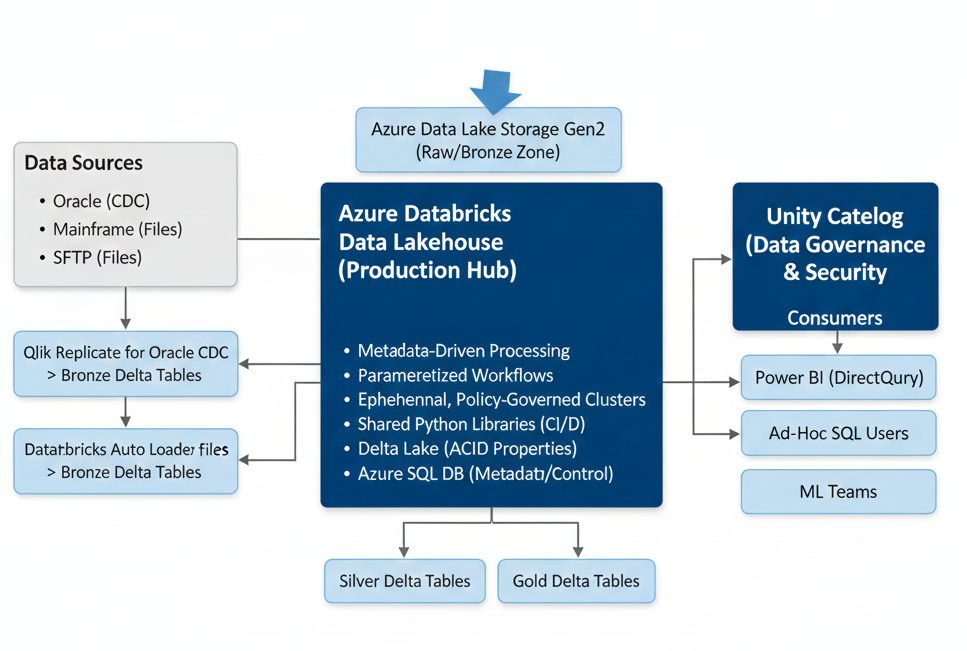

Here’s a snapshot of a successful, multi-billion-record-per-day platform I designed for a financial services company.

[Sources: Oracle (CDC), Mainframe (Files), SFTP (Files)]

|

v

[Azure Data Lake Storage Gen2 (Landing/Bronze Zone)]

|

+--> [Qlik Replicate] for Oracle CDC -> Bronze Delta Tables

+--> [Databricks Auto Loader] for Files -> Bronze Delta Tables

|

v

[Databricks Workspace (Production)]

|

+--> [Databricks Workflows (Orchestration)]

| |

| +-- Task 1: Calls `run_spark_task.ipynb` with `task_id=101` (Loads Customer)

| +-- Task 2: Calls `run_spark_task.ipynb` with `task_id=102` (Loads Accounts)

| +-- Task 3: Calls `run_spark_task.ipynb` with `task_id=201` (Joins Customer/Accts)

|

+--> [Job Clusters (Ephemeral, Policy-Governed)]

| (Each task runs on a fresh, right-sized cluster)

|

+--> [Shared Python Libraries & Transformation Logic]

| (Managed in Azure Repos, deployed as wheel files)

|

+--> [Azure SQL Database (Metadata & Control)]

| (Stores all pipeline, source, target, transform definitions)

|

v

[Azure Data Lake Storage Gen2 (Silver & Gold Zones as Delta Lake)]

|

+--> [Unity Catalog (Governance, Lineage, Security)]

| (Manages all access to Silver/Gold tables)

|

v

[Consumers: Power BI (DirectQuery on Gold), Ad-Hoc SQL Users, ML Teams]

Key Trade-offs Made:

* We used a commercial CDC tool instead of building our own because the cost was less than two senior engineers' salaries, and it gave us enterprise support.

* We built the metadata-driven framework because it gave us fine-grained control and restartability before Databricks Workflows had all its current features. Today, we would still build it to enforce standardization and reduce developer overhead.

* We chose Azure SQL for metadata because the operations team already had deep expertise in managing it.

13. Executive Summary & CXO Takeaways

For the leaders in the room, this is what matters. Your decisions on architecture directly impact the cost, risk, and long-term value of your data platform.

- Architecture is a Cost Control Lever. A good architecture uses ephemeral compute and strict policies to keep costs in check. A bad architecture leads to runaway bills that will surprise your CFO. Insist on seeing the cost governance model before migration starts.

- "Lift-and-Shift" is a synonym for "Technical Debt." A 1-to-1 migration from DataStage jobs to Databricks notebooks is not modernization. It's just moving your old problems to a more expensive platform. You will have to pay to fix it later.

- Demand a Metadata Strategy. The difference between a data lake and a data swamp is governance. A metadata-driven approach is the foundation of that governance. It reduces risk, improves agility, and makes lineage and auditing possible.

- Automation Reduces Risk. Your CI/CD and Infrastructure-as-Code strategy is your insurance policy. It ensures deployments are repeatable, auditable, and less prone to human error.

Before you approve a large-scale migration budget, ask your technical leads these three questions:

1. "Show me the diagram of how a single piece of data flows from source to report, including the orchestration, metadata, and governance layers."

2. "What specific mechanisms will prevent a single developer or job from running up a $100,000 cloud bill over a weekend?"

3. "How are we ensuring that the logic we build is testable, reusable, and not just copied and pasted across hundreds of notebooks?"

Their answers will tell you if you are on the path to a scalable, modern data platform or simply building tomorrow's legacy system today.